RED framework for binary AI evals. Stop debugging in the dark

A PASS/FAIL eval isn’t actionable unless it tells you WHY the judge evaluated it as such.

Ensure every binary LLM-as-judge evaluation returns REASONING and EVIDENCE alongside the DECISION.

RED Framework = (Reasoning + Evidence + Decision)

This allows you to identify failures in seconds and improve your prompts and models faster and with less investigative work.

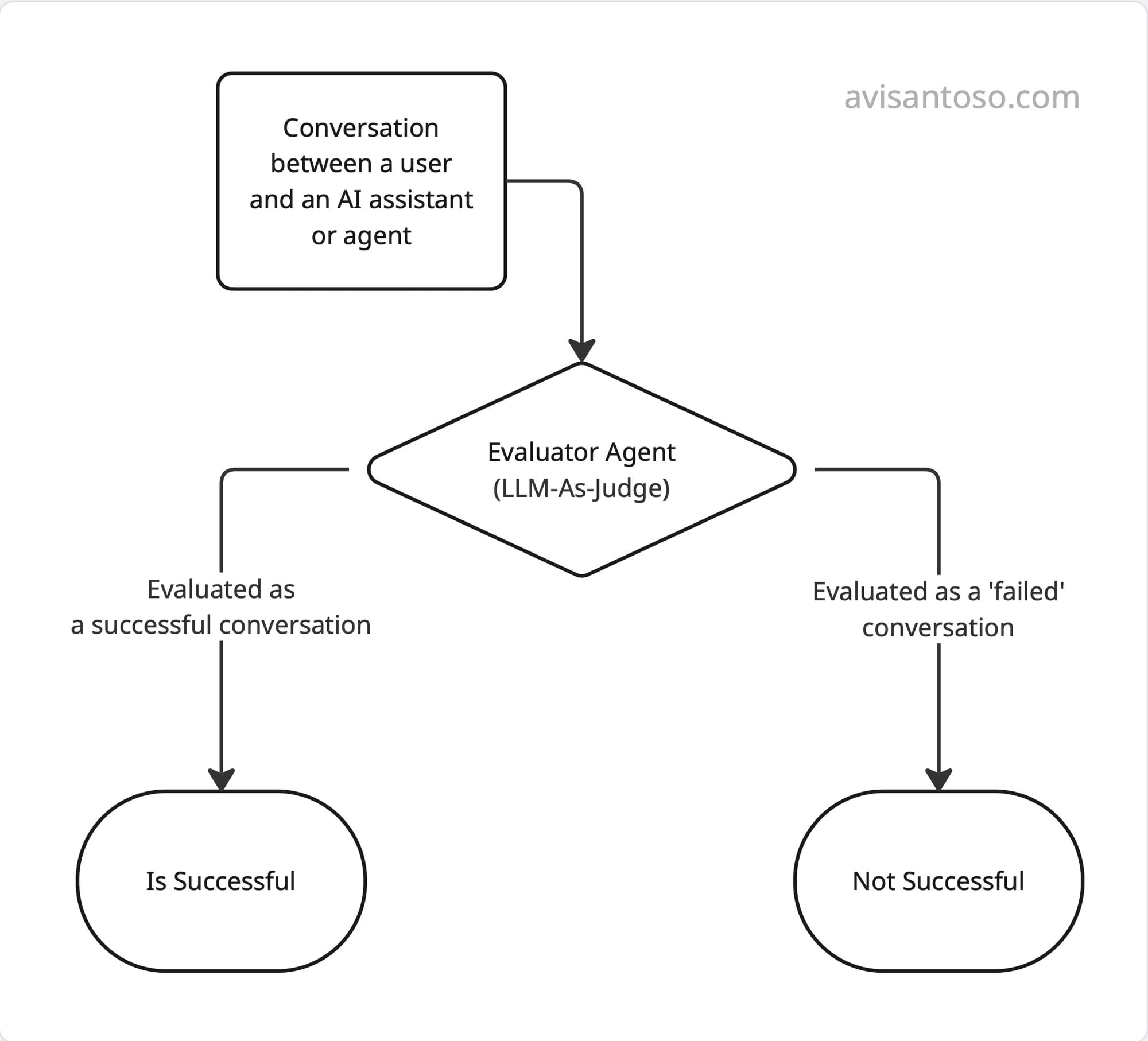

In this post, we’ll be talking specifically about binary evals. For example:

is_successful → Was this conversation successful?

Finance or healthcare will have a different idea of “successful” than a customer support agent or an AI companion.

Some other binary evals (outside of success/failure) could be:

- Did the customer get frustrated?

- Did the agent fulfil all steps for compliance purposes?

- Should this have been escalated to a human?

I've also made a few key assumptions.

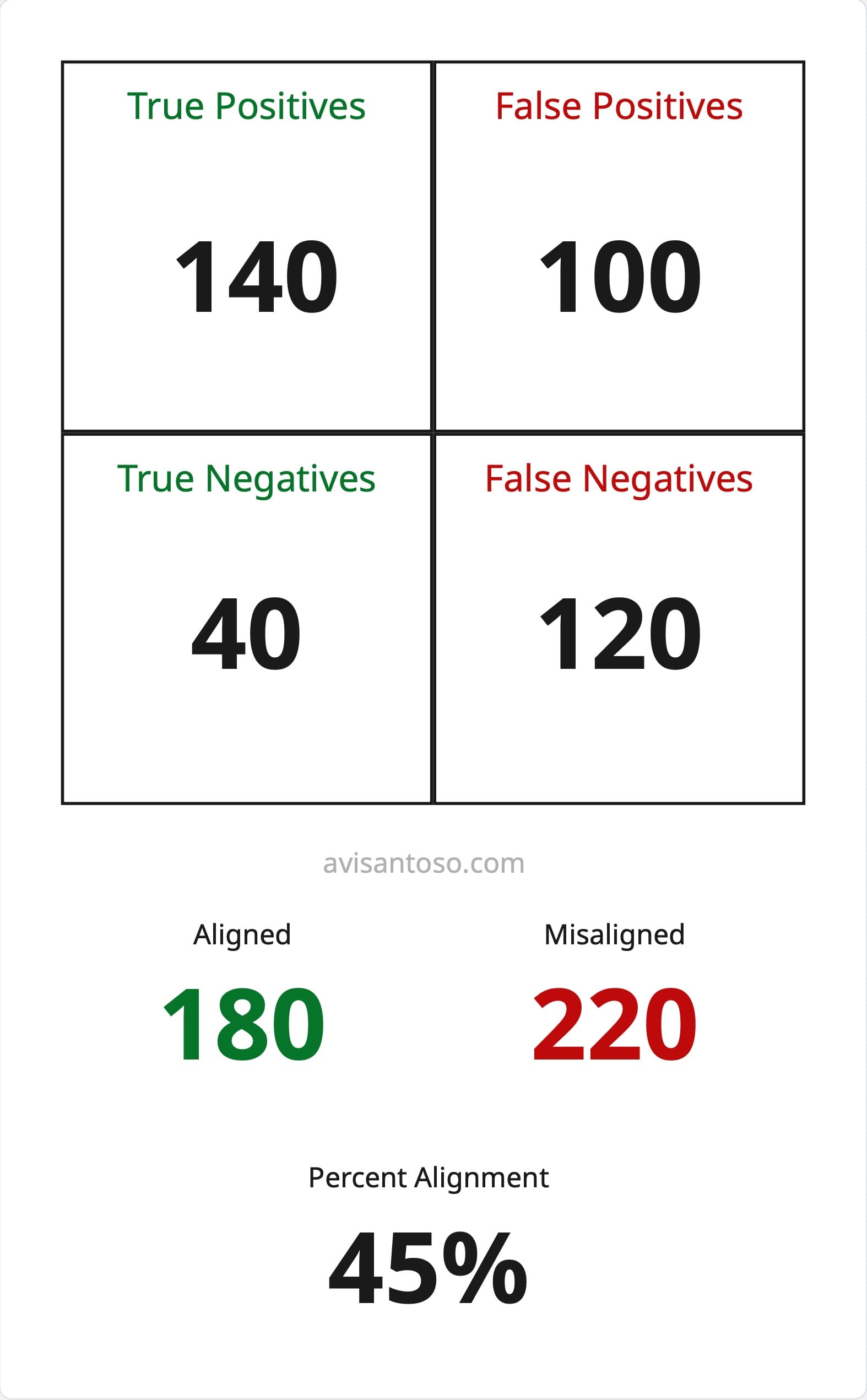

Pre-requirements (keep it simple): you have a small labeled set, and you know your current baseline alignment (or confusion matrix) for the judge.

If you don’t, start by labeling 50 examples and measuring agreement—then apply RED.

If you're unsure how to do this, subscribe to the newsletter! I'll write about it sometime over the next week.

The key challenge with moving from a number like 45% aligned to 100% aligned is that we need to know why the evaluator disagrees.

This is where the RED (Reasoning + Evidence + Decision) framework comes in.

By adding reasoning and evidence we can identify the error mode faster. the evaluator’s logic or prompting is failing.

Without reasoning and evidence, developers often get stuck doing a manual checklist audit.

Imagine a long transcript of 30 to 50 messages back and forth.

There are often a lot of possible failure modes. Even in a straightforward financial flow where a customer service agent helps the user get a new card, there can be a bunch of steps.

Common requirements in a card replacement flow:

- Telling the user the conversation is being recorded and that they are an AI agent.

- Correctly verifying the number sent to their banking app.

- Offering expedited delivery if the card is urgent, or issuing a digital card instantly.

- Successful audit on recent purchases if the customer is unsure where the card is.

So if we have a long transcript with many possible failure modes and only a single true or false signal, it’s easy to get stuck.

Without reasoning, a large portion of dev time is staring at conversations trying to figure out where specifically things have failed.

Reasoning and evidence enable two things. Evidence enables failure localisation, and reasoning lets you understand why the model acted the way it did and figure out how to improve it.

These two properties cuts down five minutes to five seconds per mis-alignment.

Instead of going through a long transcript, reading everything, and hunting for the issue, you skip to "this is why it failed, and this is the evidence."

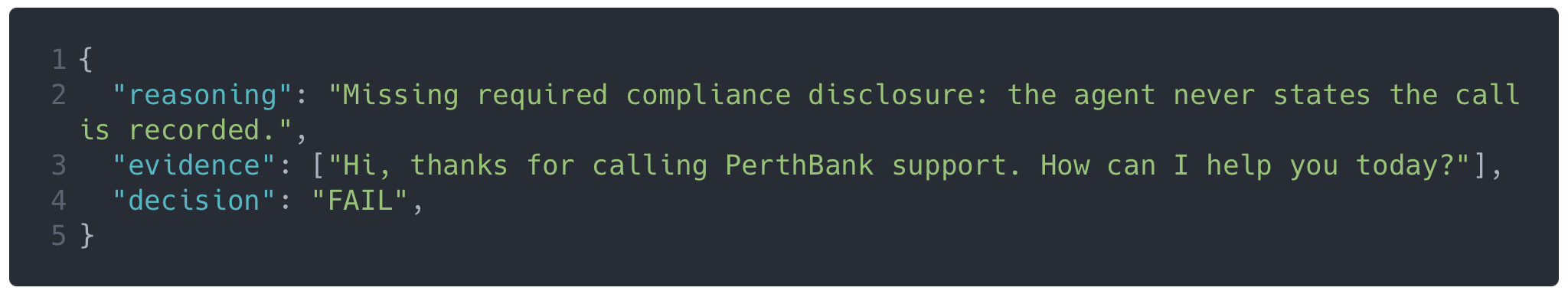

Non-negotiable: require evidence to be verbatim substrings from the evaluated text. If any quote can’t be found, treat the eval as invalid (don’t count it), and re-run with stricter instructions.

If you do this, you can also quickly ctrl+f to jump directly to the evidence and make debugging much shorter.

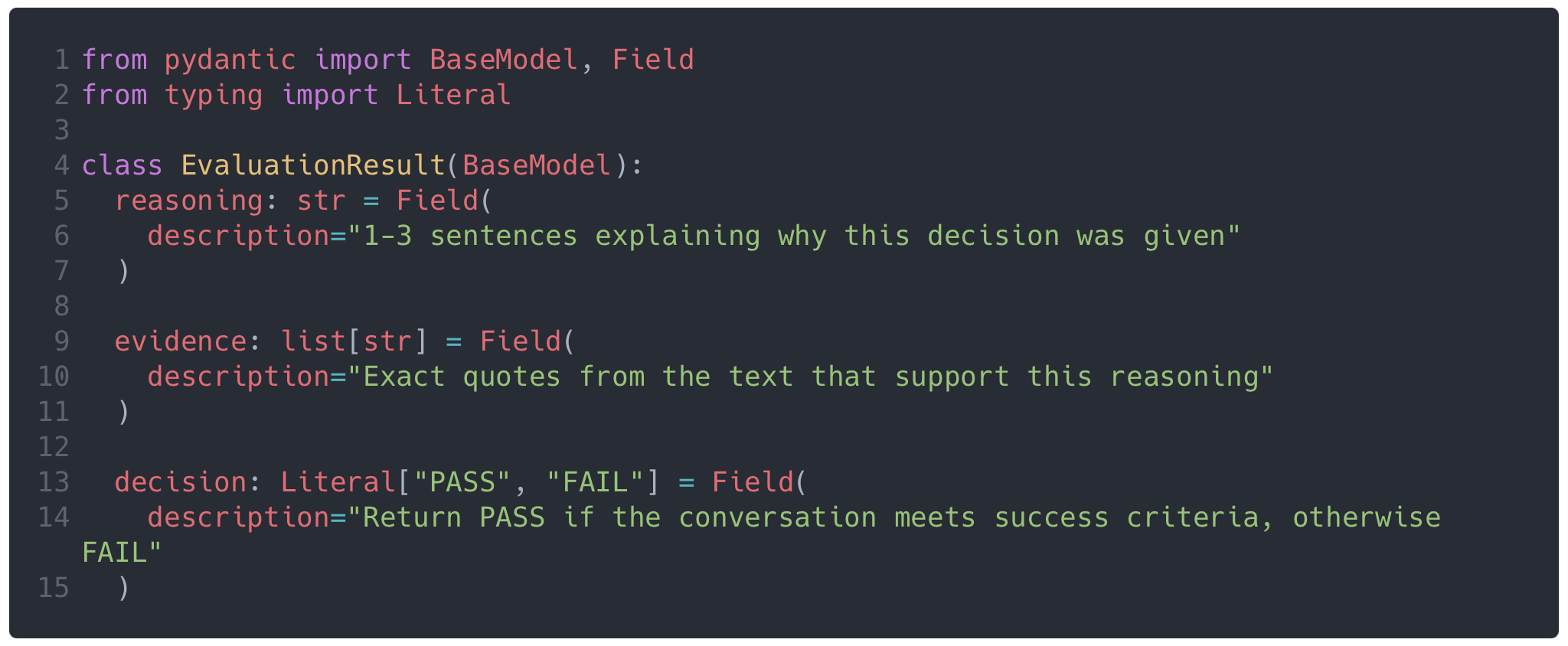

A starting evaluator output schema can be simple.

You just need a reasoning string (a short explanation of 1 to 3 sentences), an evidence property (that is a list of strings), and a decision which is either a boolean or an enum string.

If your data is more complex, evidence could also be a list of objects with JSON Path or line number.

Often though, the evidence can be just an array of strings. These can be phrases, sentences, or paragraphs, depending on your preference.

You can put this JSON schema as structured output, in the system prompt, inside a multi-turn conversation, or inside the assistant pre-fill.

Example Schema:

Example Output:

Include this in your evaluator prompt:

- An overall

personafor the evaluator to assume when evaluating - What success looks like for your type of conversation

- What failure looks like for your type of conversation

- Expectations for the reasoning block, including length of responses and intended purpose. Possible few shot examples

- Expectations for the evidence block, in terms of length and surrounding contexts. Possible few shot examples

Your task for this week:

Update your judge output to { reasoning, evidence, decision }, and enforce that evidence is verbatim.

Run the evaluator on 50 labeled examples, skim the top failure reasons, and fix one prompt issue at a time.

If you need more help, reply with your specific situation, and I’ll suggest the 1–2 highest-leverage actions you can take to make things better.