Why your agent can confidently do the wrong thing

Last week I asked Gemini CLI for a Product Requirements Document (PRD). Then got back a generic spec. It was confident, nicely formatted... yet utterly USELESS.

In fact, I'd fixed this problem before.

A few days ago, I'd already created a skill defining how to write a PRD. But Gemini never decided to trigger it, even though it was the right context.

If you're not familiar with skills, they can be considered to be "prompt packs". A glorified text file of instructions and context that would allow your agent to understand exactly what you're asking for.

Skills work very well when it's easy to trigger a skill, such as in a terminal. But what happens if you're on a phone call, or you communicate with your agent over Telegram or WhatsApp?

"The assistant wrote a PRD, but it’s not MY PRD."

"I had a file in the directory describing our research paper format, why didn't the agent use it?"

In situations where it's hard for a human to manage the currently loaded skills, this becomes a new moving part in your system. Which means it's a new way for your system to fail.

In deterministic software, if you forget to call a function, the bug is obvious. In agentic systems, the assistant will happily keep going and generate something that looks plausible.

You only notice when you start getting complaints from your customers.

In skill-based agents, you are asking a probabilistic component to remember to import its own module, at the exact moment it becomes relevant. For example, you might have a legal agent that has a few skills available:

- family-law.md

- australian-corporation-law.md

- contract-analysis.md

The intent is that the agent will itself triage which situation it's currently in, and load in the correct skill.

Unfortunately, this often results in inconsistency.

If you only remember one thing, make it this: every time you move instructions out of main context and into a skill, you create a new branch where the model can do the task without the right context.

The output will still FEEL right, so the failure hides.

So, where do instructions belong? The main context, or within a skill document?

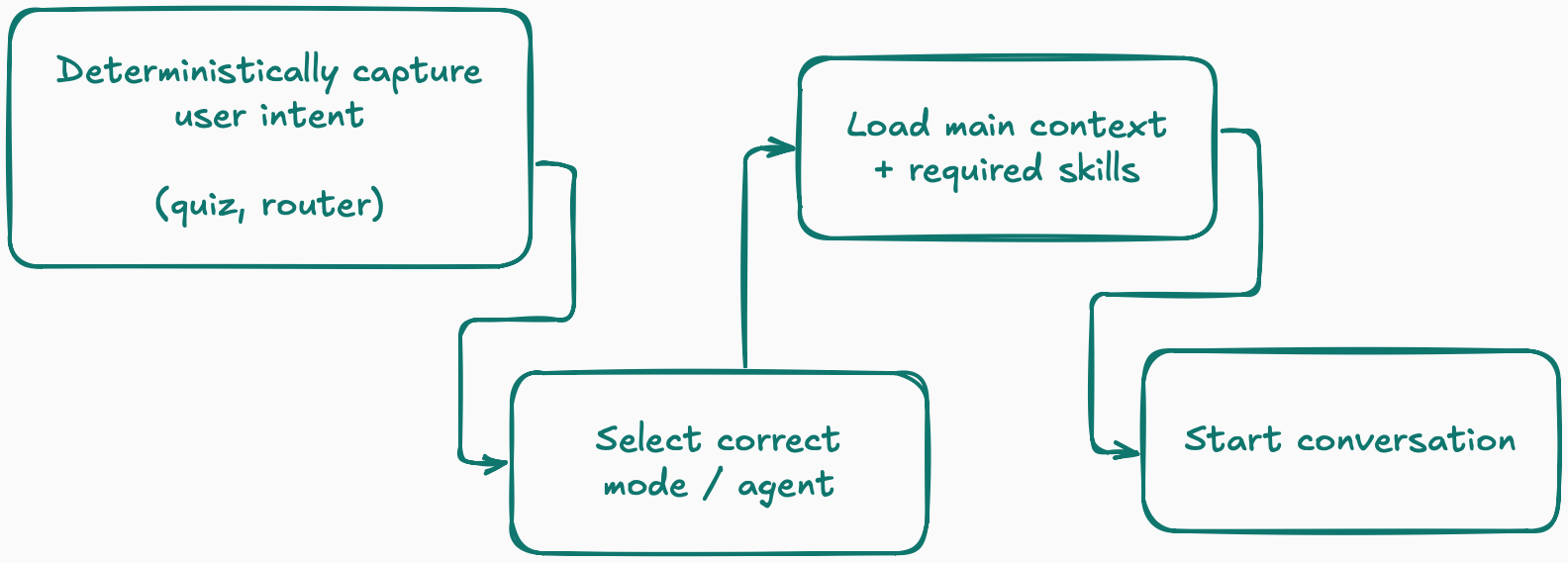

I use a simple rule of thumb. First, if you can figure out what the user wants through deterministic steps, DO IT.

Stop gambling.

Ask a small number of upfront questions, route them to the right agent, and preload the right context before the model speaks.

If you already know they came to write a PRD, don't make the model “notice” that.

Route them into the "Architect" persona that knows upfront how to make a good PRD.

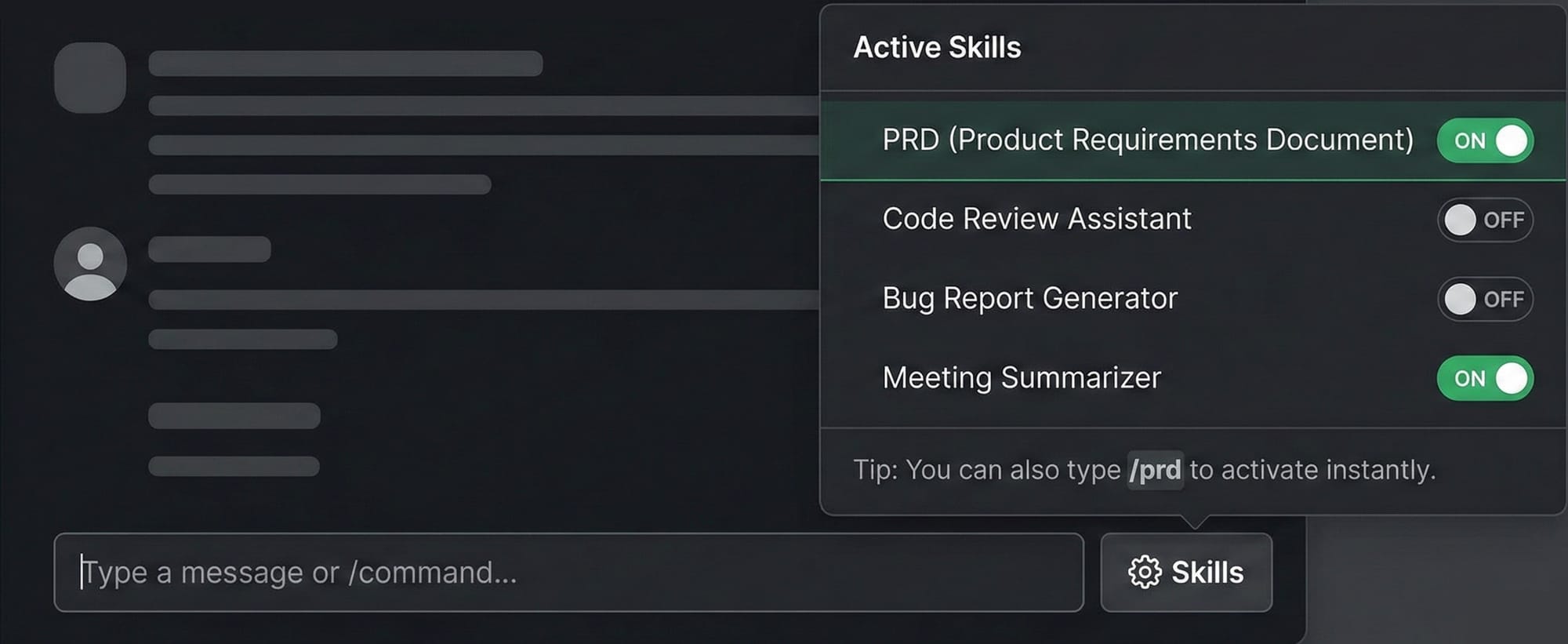

Second, if the user is a subject matter expert, give them an easy way to manage their own skills.

I'm a software engineer, so I know what I want. Typing /prd is more consistent for me than wishing the agent is smart enough to load the right context.

In fact, this is where skills shine.

You can create ONE general assistant that knows your conversation preferences, and at any time, tell it how to design, how to maintain ports-and-adapters, and how to create good unit tests. WITHOUT maintaining three separate agents.

But there's a warning here.

MAKE IT EASY TO MANAGE.

If your UX makes it hard to opt in and out of a skill, it becomes inconsistent. Make this as natural as possible.

- Terminal? Slash command.

- Chat assistant? Tab or toggles.

- Voice assistant? Routing protocol. (Press 1 for...)

Third, when you can't do deterministic routing and you can't depend on your customers to self manage their context, automated triggering is fine.

But don't treat it trivially.

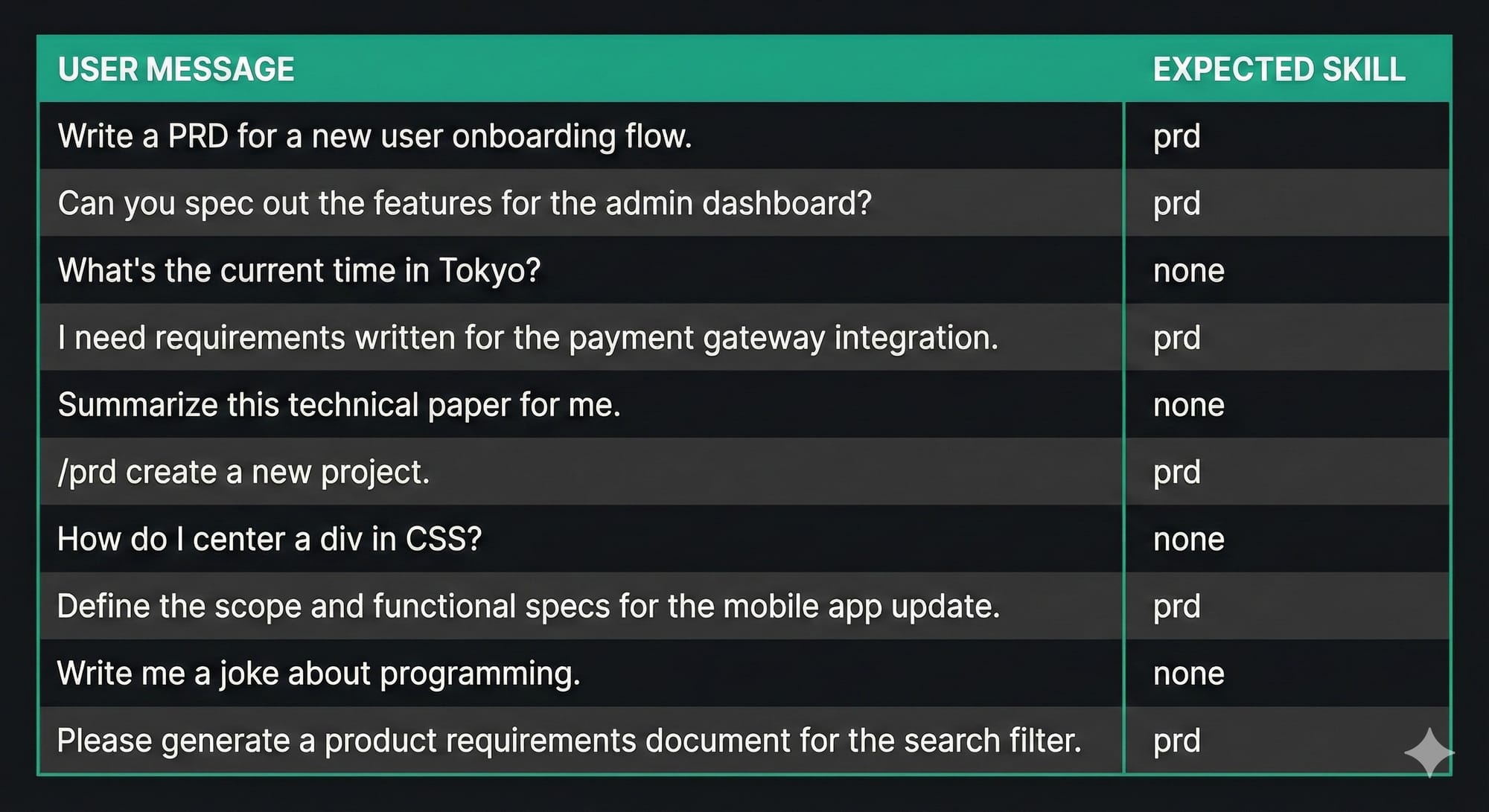

You're in essence building a classifier. This might be a separate router model, or it might be the main model with tool-choice. But in practice it is: “given this message, should we load PRD skill: yes or no.”

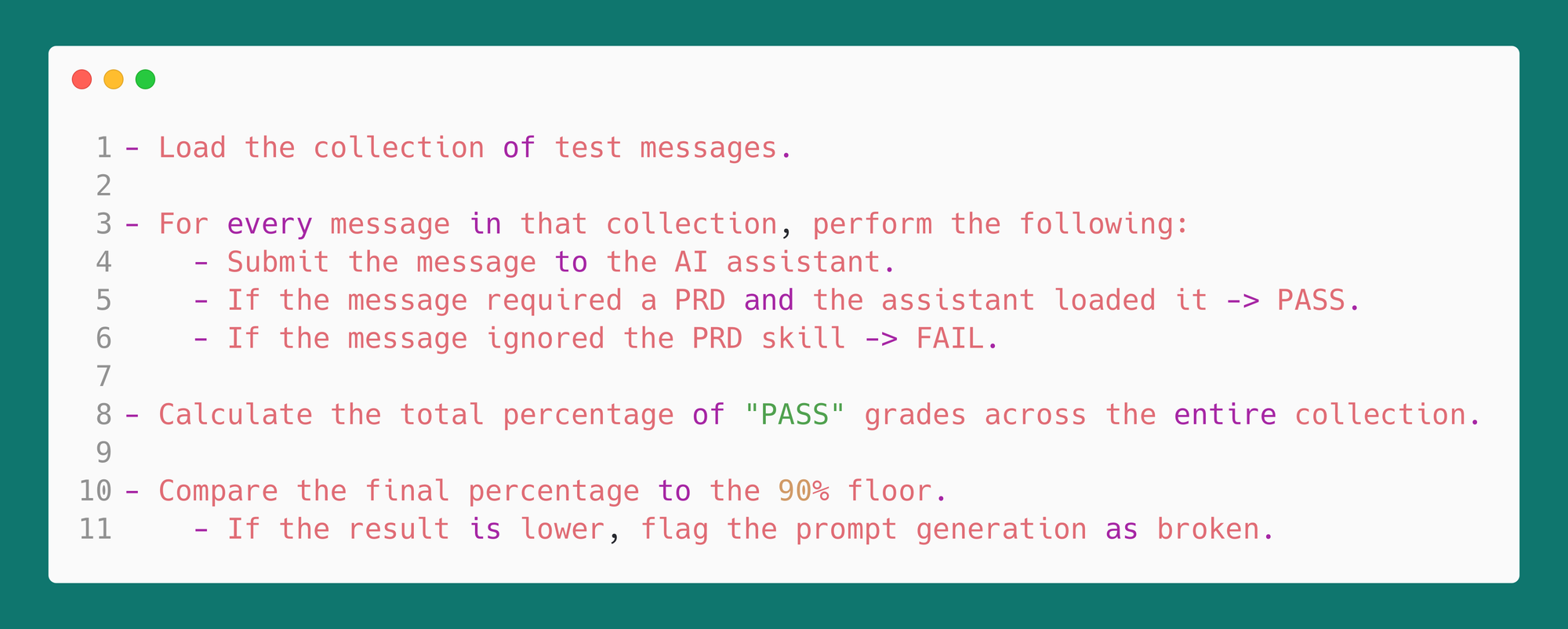

Once you say it that way, the engineering path becomes clear. You need tests, you need a dataset, and you need a target adherence rate.

I like 90 percent plus as a floor for “skill should have been called.” Below that, you will spend your life chasing ghost regressions and users will stop trusting the feature.

The evals themselves don't need to be fancy. Replay some common messages and check whether the agent called the skill before generating the document. Count the pass rate.

So, what about stuff that should always live in the main prompt?

I keep my “always-on” instructions minimal: persona, principles, and safety rails like "only look at stuff that's relevant to the task". This shouldn't depend on a skill firing, because it's supposed to shape every response.

As a bonus, provide the most commonly misunderstood domain vocabulary and concepts in your context. If you're in physics, "work" means something different than in other contexts. "Customer" means something different for an IT team compared to the sales team.

And if you can't get your evals passing consistently for a given workflow, don't leave that information living in a skill that might not load. You want it in the root prompt to reduce the error rate.

In summary: if the user knows what they want, route deterministically and load the right context before the model speaks. If the user is a power user, let them self-select skills and personas naturally, and avoid forcing them into one over-specialized agent. If you can't do either, automate triggering, but don't ship until you can prove it fires when you expect it to, 90% of the time.